There is an urgent need to review the UK’s system of communicable disease control administration and its public health laws

This blog was originally published on the LSE Politics & Policy blog

In the midst of a lethal pandemic, the government controversially axed the main public health body (Public Health England) and announced the creation of yet another bureaucracy, designed by management consultants with no expertise in public health. History shows that without a clear overarching strategy and laws, these ad hoc reforms are likely to further hamper the UK’s ability to protect the population.

Experts have been warning for decades about the dangers of a system of communicable disease control administration in the UK which is confused, irrational, and rests upon an outdated sets of laws, none of which have been framed to deliver a clear set of policy objectives. In 1988, Sir Donald Acheson, the former Chief Medical Officer described a system which was ‘positively baffling’, in 2003 a House of Lords Committee asked the government to draw a map of how the system worked, but it was unable to do so. Our own study into pandemic preparedness in 2013 identified a lack of clarity about ‘who does what and how the system is co-ordinated’.

The last time any UK government published a strategy document relating to infectious disease control was 18 years ago in 2002. That review (Getting Ahead of the Curve) established the Health Protection Agency, a public body charged with co-ordinating a response to a range of health threats. In 2012, the Agency was scrapped as part of the Lansley reforms to the health service to be replaced by Public Health England, the body which is now to be disbanded.

The main law governing the control of disease in England and Wales – the Public Health Act 1984 – has also been left unreformed by policymakers. Whilst the Act was updated 12 years ago to incorporate the International Health Regulations, the basis of our public health law is in essence little different to the Sanitary Acts of the Victorian era. The legislation grants highly authoritarian powers (to detain individuals, close businesses etc.) to local public bodies but it has not been updated to reflect the now radically different machinery of government which has emerged from the constitutional revolutions of the past two decades. The legacy of this failure to modernise the system in line with a coherent strategy is now being seen in the UK’s tragically hapless and uncoordinated attempt to control the virus. Take for example, the inability of local authority public health directors to exercise control over outbreaks in their local areas. Whilst the pandemic is often viewed from a national or global perspective, it is actually made up of hundreds of thousands of local outbreaks.

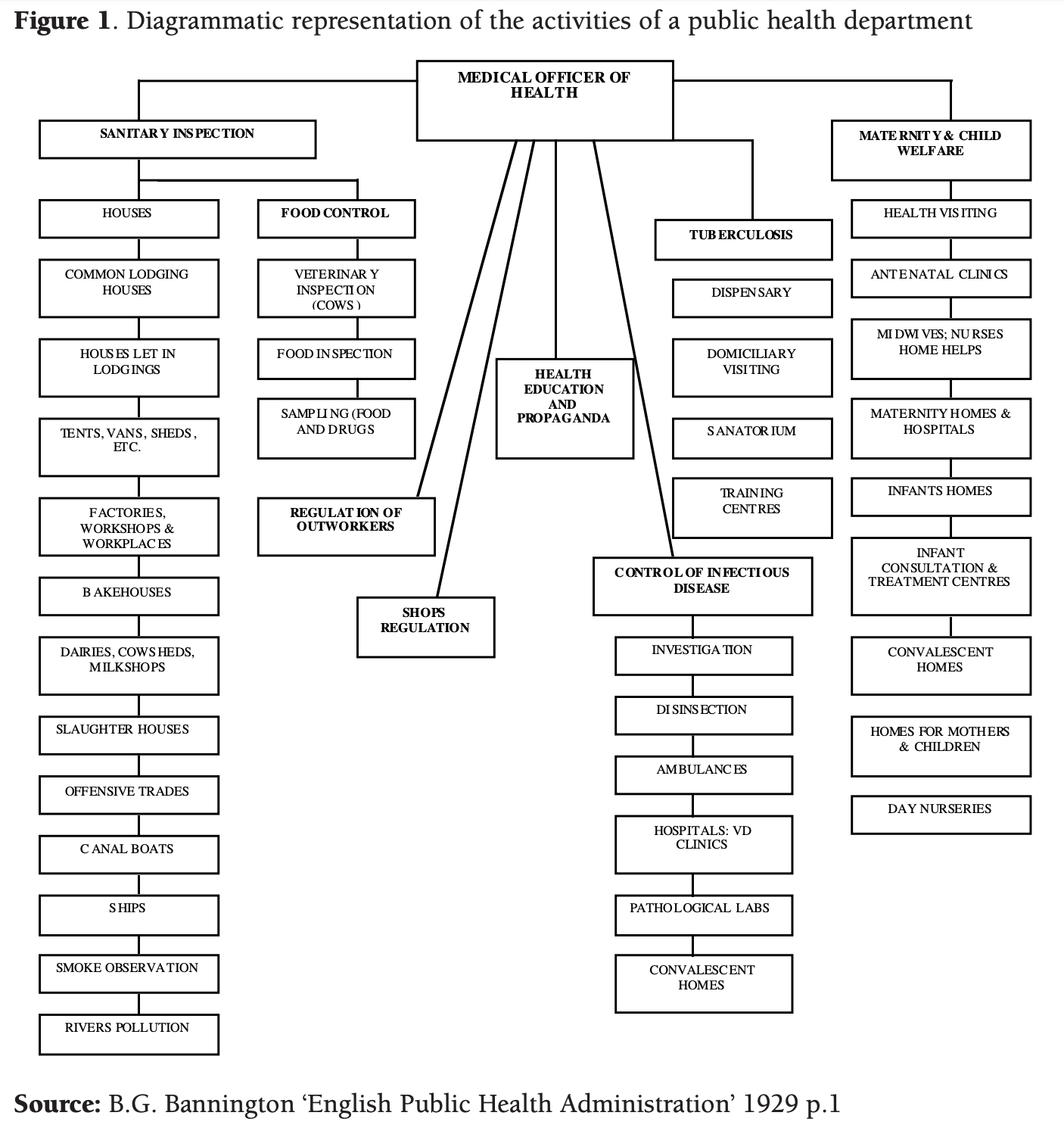

The Victorians recognised this fact about infectious disease and so gave powers to control outbreaks to Medical Officers of Health based in local authorities. In the early twentieth century, these powerful public servants sat at the top of an impressive public health infrastructure ranging from laboratories to health visiting to sanitary inspection (see Figure 1).

However, up until very recently, Directors of Public Health in England have struggled to exert the necessary authority to protect their local communities. This in part stems from the fact their disease control powers under the Public Health Act 1984 have in most cases been delegated to the regional teams of Public Health England – an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care which answers directly to Ministers. It is only in the summer of 2020 that the Coronavirus regulations gave specific legal powers to Directors of Public Health to take action to close premises, ban public events, and close outdoor spaces without the need to resort to a magistrate.

Worryingly, vital data about infectious diseases was not being sent to Directors of Public Health, in contravention of the law on notifiable disease, a law which dates back to the 19th Century. Instead, the data appears to have been held by Public Health England, but not shared with Directors for data protection reasons. And whilst Directors of Public Health are now more empowered by the new regulations, this hastily put together legislation (which was passed without Parliamentary debate) has not been framed in such a way as to resolve the tension between national and local responsibility for control of the virus, as has been witnessed by the confusion and timing over the new local lockdowns in Leicester and the North West of England.

Moreover, the legal framework cuts locally elected Mayors out of the picture. Even though the Mayors of Greater Manchester and London have played central roles in coordinating and managing the pandemic response in the UK’s two largest conurbations, neither has any clear powers or statutory duties relating to infectious disease.

Looked at from a UK wide perspective, the unstable devolution settlement compounds the problems of co-ordination and blurs the picture about who is ultimately in charge. Whilst the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 provides Ministers in Westminster with emergency powers covering the whole of the UK, the current devolution settlement has allowed elected representatives in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales to take different approaches to managing the pandemic. Thus, decisions about school openings, care homes, the wearing of face masks and the relaxation of lockdown have been approached differently across the four nations.

However, it is unclear whether the current constitutional settlement will be able to accommodate a fundamental difference in policy objectives towards the pandemic. If the Westminster government’s approach is to live with COVID 19 – as appears to be the case – it will not also be possible for the governments of Scotland and Wales to also seek to eradicate the disease, which is their stated policy goal. This is due to the fact that decisions about entry into the UK and population movement across the internal borders of the UK are ultimately made by Ministers in Westminster. In addition, Westminster still holds the economic levers which determine the sustainability of lockdown policies in the four nations – most importantly, the vast economic safety net which includes sick pay levels and the furlough scheme. Any reduction in these benefits impacts significantly on local attempts to prevent potentially infectious people from working.

All of this confusion about who is responsible for delivering the basic public health response has been made worse by the UK’s fetish for outsourcing and privatisation. In England the government has handed over responsibility for contact tracing to private companies, who in turn have sub-contracted these functions to other companies. There is currently almost no transparency about what these companies have been asked to do, or to whom they are answerable.

Attractive as it might be politically, axing one public body and replacing it with another is not the same as developing and implementing an effective strategy for disease control. To be effective, any such strategy needs to set out clear policy objectives, while the law and the administrative units charged with exercising these powers need to reflect these objectives, with clear accountability lines set out. Mechanisms for resolving disputes between the local, national, and devolved administrations should also be put in place, with a framework for balancing the competing interests of population health with individual human rights. A rational approach would also include the European Union in recognition of the fact that infectious diseases do not respect borders and to combat the confusion over quarantine rules for holidaymakers.

To date, the study of communicable disease control administration has been a minority pursuit. However, it is increasingly clear that getting this aspect of public administration right, is key to the functioning of almost every other aspect of the UK’s social, political and economic life.