Between May 2013 and February 2016 a heated argument took place between Kingsley Manning , the chair of the Health and Social Care Information Centre (now called NHS Digital) on the one hand, and the Home Office and the Department of Health on the other. At stake was the HSCIC’s independence as an Executive Non-Departmental Body responsible to parliament, not to any minister, and its trustworthiness as the guardian of the personal details of every NHS patient in England.

After his appointment as chair in May 2013 Manning discovered that since at least 2005 the HSCIC and its predecessor, the NHS Information Centre, had been giving details of patients’ present and past addresses and GP registrations to the Home Office, to enable it to trace and deport people who were living in Britain without the right to do so. This appeared clearly to be in breach of the HSCIC’s ‘statutory duty to ensure that the information we hold in trust for the public is always kept safe, secure and private’. But the Home Office, supported by the Department of Health, insisted that tracing ‘illegal immigrants’ was a public interest that overrode any other. The outcome was a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between NHS Digital, the Department of Health and the Home Office, which specifies that NHS Digital will hand over the information requested by the Home Office for patients who have ‘breached s.24 of the Immigration Act 1971’, if all other ‘reasonable avenues’ (such as the Department of Work and Pensions and the DVLA) have been exhausted. The memorandum came into effect on 1 January this year.

In an interview with the Health Service Journal published in February this year Kingsley Manning described how the Home Office and the Department of Health resisted his demand to know the legal basis for what was going on, and to make it public. And on the eventual MoU his comments were as follows: “There is no provision for transparency, no provision for oversight or scrutiny and there is no role for the National Data Guardian. Nor is there any provision to alert patients to the possibility that information from their NHS patient record could be passed on to the Home Office.”

Two questions need to be asked about the memorandum. First, what is the legal basis for the breach of confidentiality it normalises? The minutes of an NHS Digital Board meeting in August 2016 record that ‘NHS Digital had received internal advice that there is a high of risk of legal challenge but that there was a robust legal defence’. By the time of the Board’s November meeting this had become ‘we have established the legal basis for data flows to the HO [Home Office]’. Second, whom does the MoU’s codification of procedures protect? Evidently, at least NHS Digital. The Board insisted that the request form specified in the memorandum to be used by the Home Office should ‘note in the form that the form provides an explicit audit trail in the event of challenge or query’.

NHS Digital may still refuse to hand over information if it is not satisfied that there is a public interest in doing so. In practice, however, a public interest appears to be established if the Home Office says the details are those of someone who is in breach of the Immigration Act and can’t be traced in any other reasonable way.

The scale of these ‘data flows’ is not insignificant.

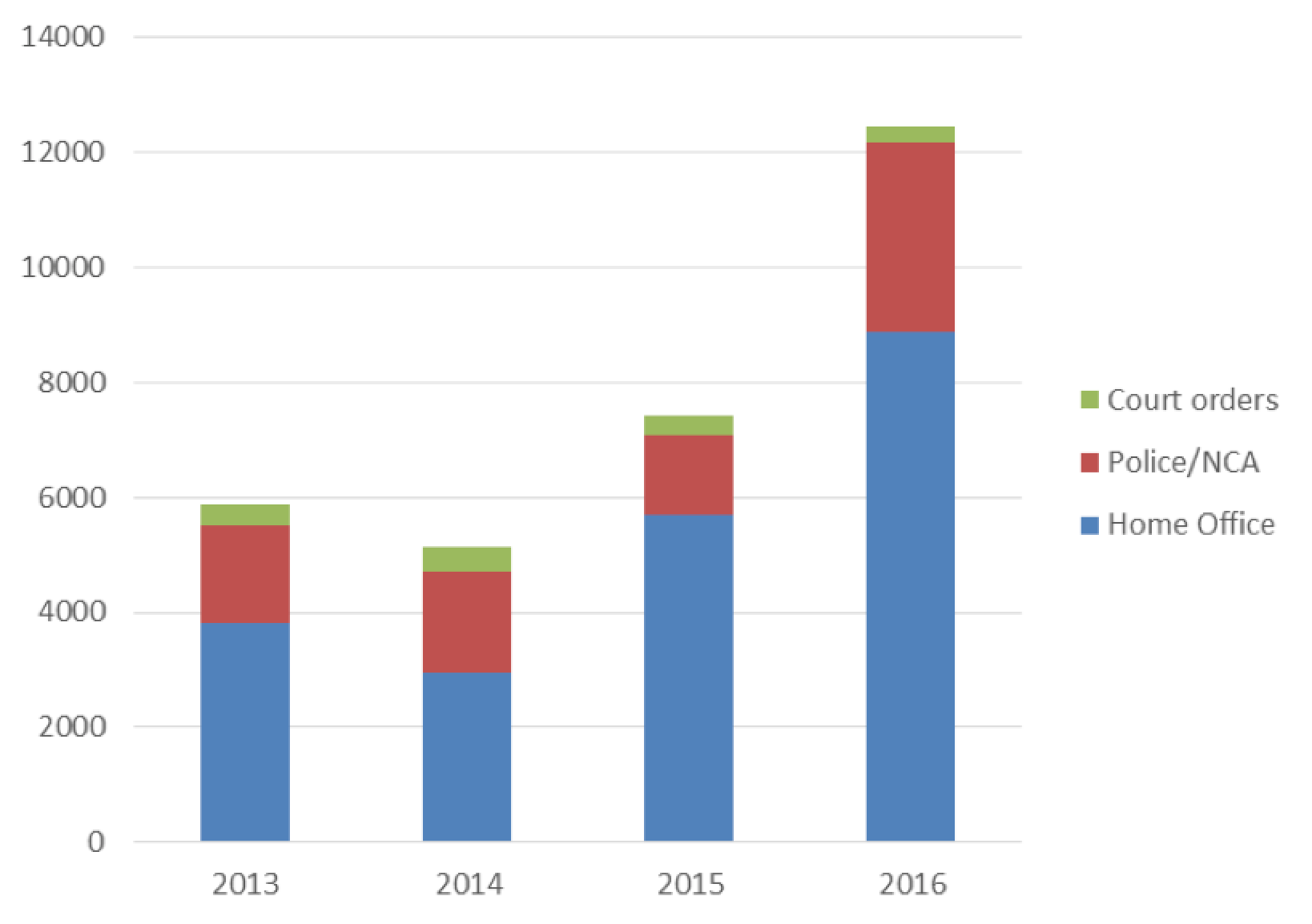

Requests for patients’ data received by NHS Digital (HSCIC) 2013-2016*

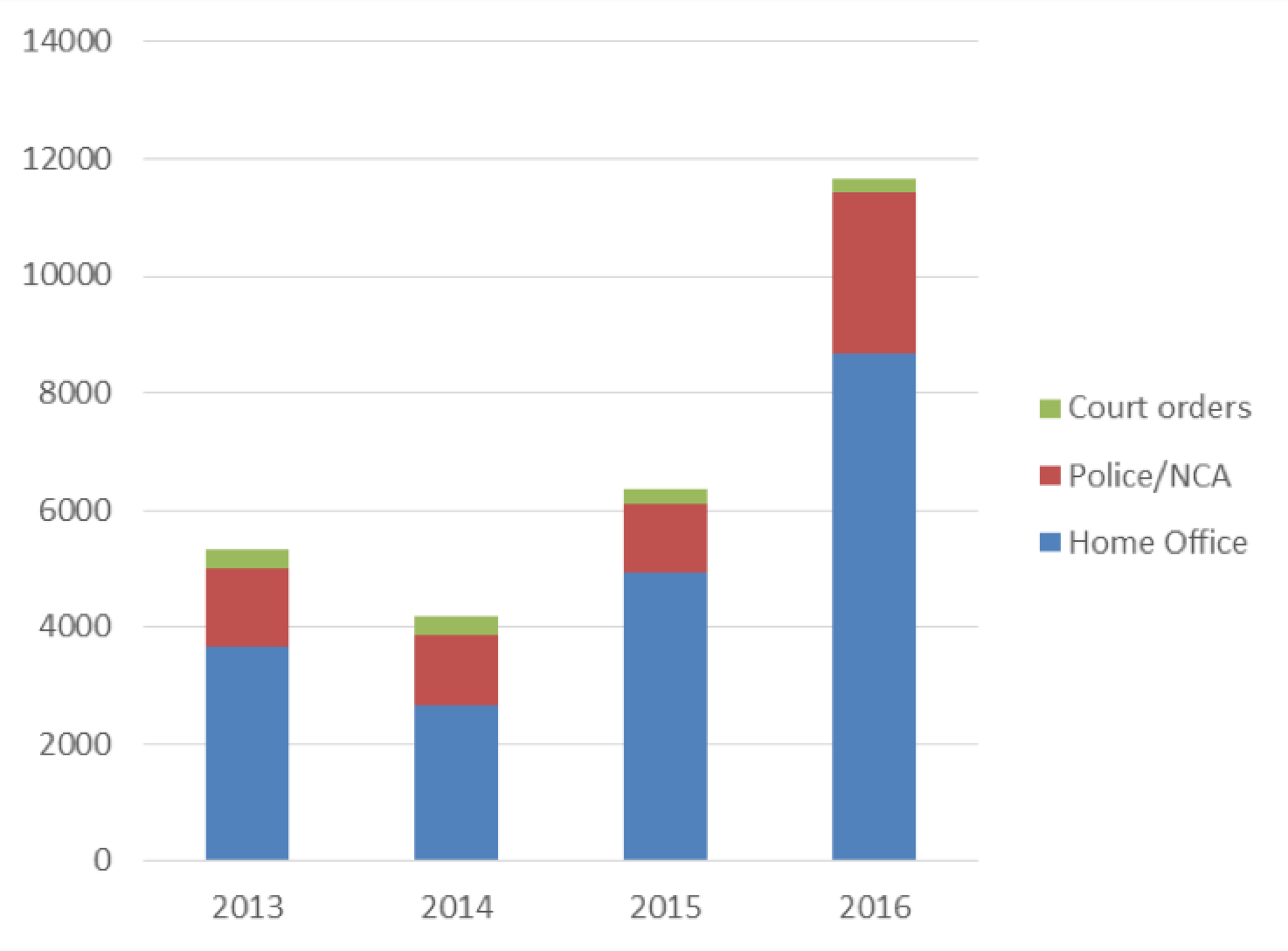

Requests for patients’ data accepted by NHS Digital (HSCIC) 2013-2016*

The data release registers show that patient data are also routinely given to the police and the National Crime Agency (NCA), and to the courts in response to court orders (presumably relating to serious crime), without any MoU; and in 2016 the number of requests from the NCA (mainly) and the police increased by 40%, compared with 2015, accounting for a quarter of all the personal data that NHS Digital handed over last year – on what grounds, in these cases, and on the basis of what authority, we do not know. The effect of a memorandum of understanding seems simply to formalise an unaccountable practice with a debatable basis in law, but which the government wishes to continue. It will be interesting to see if this is compatible with the far-reaching new data protection regulations which will come into force in June.

The risk to public health from handing over personal information that people have been assured is confidential is obvious. Kingsley Manning told the HSJ that ‘My key concern has always been that highly vulnerable people will be deterred from accessing the health system because they are worried that their information will be shared with the Home Office. This puts their health at risk and the health of the public at risk, since infectious diseases such as tuberculosis will become harder to treat.’ He could have gone further. It is estimated that some 600,000 ‘irregular residents’ live in the UK (including children who have been born here and are not immigrants, legal or otherwise). NHS Digital‘s collaboration with the Home Office to help it find and deport them is bound to become common knowledge in these circles, not to mention among those wanted by the police and the NCA. A logical consequence is avoidance of the NHS and the development of an underground private medical system, vulnerable to exploitation and extortion. (The health charity Doctors of the World runs free clinics in London and Brighton, but mainly to help people to get access to needed care from the NHS, whereupon they become liable to have their data shared.)

NHS Digital is a critically important resource for high quality health care and its 2,700 staff have a well-earned reputation for competence and courtesy. But its independence, and public trust in its determination to protect patients’ privacy, have been seriously compromised, if not destroyed. The message sent by the MoU is, as a briefing by Doctors of the World points out, that ‘when it is politically expedient to do so, our personal information will be shared’. Trust can be restored only by ending the use of NHS Digital (along with landlords, schools and universities) as an agency of law enforcement. It would seem from his strongly-worded criticism that this was what Kingsley Manning wanted, and it is to his credit that we know as much about it as we do.

But why was it so relatively easy for the Home Office to have its way? Manning told the HSJ that he ‘came under immense pressure to leave matters as they were… The threat was that if we pursued this line of questioning we would be deemed to be an ‘insufficient partner within the system’. An ‘insufficient partner within the system’? What exactly was the threat in that? ‘If I didn’t agree to cooperate they would simply take the issue to Downing Street.’ How terrifying! The Board of NHS Digital have a statutory independence from government and, one would think, a moral duty to defend it. Manning announced his resignation in February last year, without giving any reasons. The memorandum was signed by his former colleagues in November.

* Source: NHS Digital data registers. In February 2017 the registers covered only the last nine months of 2013 and the first eleven months of 2016. To avoid understating the data for these years, data for the missing months have been added based on the averages for the reported months in the respective years.

Support Our Work

CHPI is the only truly independent health think-tank dedicated to the founding principles of the NHS. To continue our work keeping the public interest at the centre of health and social care policy, we need your help.

Please support CHPI so we can continue to impact the health policy debate.